The other day, I received an email asking me what my current definition of stuttering is...

My first thought was, well, do you have an hour? There's so much to say!

Plus, it's sort of a work in progress, as my understanding is always changing based on recent research and new insights from people who stutter.

The inquiry challenged me to type out my current thoughts, and I thought I'd share them with all of you. Fasten your seatbelts, here goes!

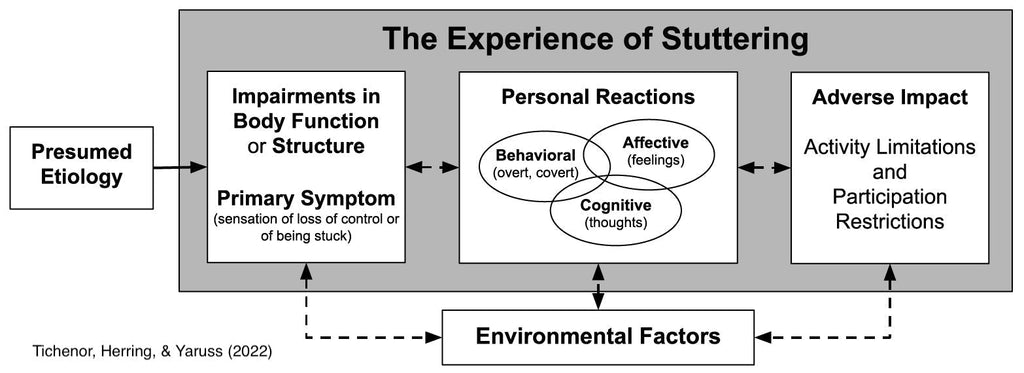

The background for my current definition of stuttering is probably best found in the image associated with this blog post, which is drawn from a couple of articles that my colleagues and I wrote about defining stuttering.

The articles actually reflect the definition of stuttering as explained to us by adults who stutter. The model that we describe is based on the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (WHO, 2001).

The basic idea is that the experience of stuttering has multiple components.

One of those components is the perception of being stuck, or of having difficulty moving forward in speech. That could be defined as the “moment” of stuttering - the instant when the person knows exactly what they want to say, but they have difficulty saying in that moment. They feel as if they have lost control of their speech mechanism.

That sensation of feeling stuck can lead to the moment of disrupted speech fluency that a listener might perceive.

That sensation of feeling stuck can also result in wide range of consequences.

One set of consequences has to do with how the speaker reacts to their stuttering: how they feel (affective reactions), how they act (behavioral reactions), and how they think (cognitive reactions) -- the so-called ABCs of stuttering.

- The feelings might involve embarrassment, frustration, shame, anger, etc…

- The actions might involve physical tension or struggle as they try to get the words out, or avoidance of a sound of word. This is also where the repetitions, prolongations, and blocks come in, as the speaker attempts to cope with the sense of being stuck and move forward in their speech.

- The thoughts might involve negative self-esteem or self-confidence, and these thoughts may be influenced by a tendency toward rumination or repetitive negative thinking.

These “personal” reactions reflect the person’s level of acceptance of their stuttering, and they develop based on a host of other aspects of the person’s experiences and personal characteristics.

Another set of consequences has to do with how the listener reacts to the stuttering: we have a lot of evidence that listeners respond negatively, including laughing, looking away, giving “the look,” filling in words, or saying other unhelpful things, etc. These “environmental” reactions shape a speaker's personal reactions and influence the impact that the speaker experiences in their life.

The final set of consequences relates to how the sense of being stuck, the personal reactions, and the environmental reactions combine to cause an individual to experience difficulties in their lives related to their communication. For example, they may experience limitations in their ability to engage in activities that they want to perform, especially those related to talking (though ultimately stuttering can affect more than just speech-related activities). Thus, they may have difficulty introducing themselves, talking on the phone, giving a presentation, making small talk, etc.

These limitations in daily activities can ultimately be associated with a broader restriction in their ability to participate in their life the way they want to. They may not pursue their life goals in the same way as they otherwise would like to do, and this can affect their social or civic engagement, their pursuit of educational or career goals, and their relationships with family and others.

Taken together, we say that stuttering is more than just stuttering, as we seek to reflect the fact that the experience of stuttering involves much more than just the production of disrupted speech.

Another important part of this approach to stuttering is the recognition that people who stutter have brains that are subtly different from the brains of people who do not stutter. These neurological differences are what lead to the loss of control that the speaker sometimes experiences when talking.

Given the neurological differences, we can say that the sensation of being stuck is actually a normal and expected aspect of that person’s language formulation and speech production, because of the underlying neurological differences that they exhibit.

Taking this approach can help to reduce some of the stigma surrounding stuttering, because we can come to recognize that the speaker is not doing anything wrong when they stutter. True, those underlying neurological differences can be defined as a “disorder,” from a medical perspective, and we can use that language in context such as qualifying people for therapy and third-party payment.

And, certainly, many people who stutter want to learn ways of navigating moments of stuttering more easily so that they can say what they want to say with less physical tension and struggle. Thus, we can and should still offer therapy for people who stutter who want it, and that therapy can still address speaking skills (among all of the other aspects of the stuttering experience described above) if and when that is appropriate for a given client.

From a personal and societal perspective, however, we can also recognize that the disruptions that we see in the speech of people who stutter, simply reflect a variation in the ways that people can talk.

That is why we say that stuttering is verbal diversity — that is, stuttering is one of the many ways that people talk, and we do not need to view it as being inherently bad or wrong. It is simply different, and viewing it in this way can help people who stutter—and people in society—learn that it is okay to stutter.

Whew! That was a lot.

Inherent in this definition are several of the key facts that I want people to know about stuttering. To summarize:

- Stuttering is more than just stuttering: living with stuttering involves more than just the production of speech disfluencies

- Society plays an important role in determining the negative impact that people who stutter experience, so it is important for us to advocate for greater acceptance for people who stutter.

- Stuttering is verbal diversity: it is one of the many ways that people can talk, and it does not have to be viewed as inherently bad or wrong

- We can still do therapy with people who stutter: This includes therapy involving speaking skills, though that therapy should also address an individual's entire stuttering experience

- It’s okay to stutter - really, it is!

So...those are some current thoughts... Of course, these ideas will continue to grow and change as I learn more, but in the meanwhile, I hope that this information will help some of you as you are thinking about your own understanding of the definition of stuttering.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(NOW...if you're wondering how to explain all of this to parents and other caregivers--or to children who stutter--stay tuned. I'll address that in a future blog post.)